When Ashley Miller (’15, Interdisciplinary Studies) transferred to UC Berkeley as a junior in Fall 2012, she had two goals in mind: to study abroad (despite the tight timeline) and to go somewhere entirely different than anywhere she had been before. She chose Kenya. With funding from UC Berkeley’s Miller Scholars program, she planned to research the effects of Kenya’s 2003 free primary education policy. Unfortunately, a national teachers’ strike in 2013 made interviewing teachers and families difficult. As a result, she spent more time, on and off campus, befriending the Kenyan students involved with her program at Kenyatta University, and a remarkable story unfolded.

One of Ashley’s new friends, Louisa Mwenda, invited her to her home during the program, and Ashley felt an instant chemistry with her family. After the program ended, Louise brought Ashley to a family wedding celebration in Kaloleni, a town in the coastal province near the Indian Ocean. In addition to enjoying the celebration, Ashley learned about the largely agricultural area’s severe water problems in her conversations with Louisa’s relatives. Over time, the concept of an ambitious project emerged: bringing water to the local primary school and the surrounding community. The community members were motivated to remedy the situation, and Ashley wanted her experience in Kenya to be beneficial to others, not just to herself.

Inspired and back in Berkeley, Ashley started fundraising. She wrote grant applications and received generous campus support from several sources, including the Blum Center’s Big Ideas program and the Center for African Studies. She was also awarded the 2014 Donald A. Strauss Scholarship, which at the time provided a $10,000 project grant to pursue a self-initiated public service project. Ashley remembers that it was “by far the largest single funding source we had received. Suddenly we went from having a theory for the project to actually being able to make it a reality.”

Ashley’s project—“Maji Yaje Kwanza: Piped Water and Sanitation in Kaloleni Kenya”—proposed to develop the infrastructure needed to provide water and sanitation access to Mihingoni Primary School in Kenya. In addition to fundraising, she also sought logistical advice from faculty and staff in the Haas School of Business, Blum Center for Developing Economies, and the Energy Resources Department.

Ashley returned to Kaloleni in summer 2014 armed with practical knowledge and $21,000. The team’s ambitious pilot project included constructing hand washing sinks, water taps, and a water kiosk to serve the community on the edge of the school grounds; installing two 10,000-liter water tanks in case of shortages; and laying a 2.5-kilometer water pipeline. Between 150–200 community members were hired to do the work, in partnership with the local water municipality. The project was projected to serve roughly 5,000 people.

The team successfully enacted all needed infrastructure, and there was a launch celebration with the Area MP, Office of the President, school staff, and the children’s families. Tragically, however, the water pressure turned out not to be strong enough to provide water service to the school, and worsening drought conditions proved that the municipal water source—and some local leadership—were not reliable. The team ultimately determined that digging a borehole (underground well) to connect with the new infrastructure would be the only way to ensure consistent water service.

Again, Ashley drew on her Cal network. A successful Berkeley Crowdfunding campaign in 2018 raised $12,000 to establish the borehole. Despite assurances about the well’s location from local hydrogeological surveyors, the diggers never hit water. Ashley recalls: “When the huge drilling trucks arrived at the school, so many kids and parents were there, dancing and singing. Keep in mind, this is four years after the initial project implementation. We’d all been waiting, with waning hope, for this moment. A few hours in, drillers hit a small gush of water, but it wasn’t the aquifer the geologist expected. We continued to drill deeper 250 meters into the earth and all stood there, at this point in darkness. I couldn’t look any of the community in the eye, especially the kids. It was indescribably devastating.”

Just before Christmas, Ashley and the team called a town meeting. She wrote up the entire project history and asked Louisa’s uncle, a teacher at the school, to translate it into KiGiriama. She recalls: “I sat and listened to him read, and could finally look in the community’s eyes: I saw all the anger, disappointment, frustration, and heartbreak that we too were feeling. As painful as it was, it was a collective mourning, and in that way was very unifying.” With the community’s support, Ashley and the team made the emotionally difficult decision to step back from the project and hand it over to the school to advocate to local leadership for completion. The team had done all it could with its limited resources and positional power.

Four years later, Ashley still hopes to see water running through the pipes to the school but has no idea when it will happen, especially with the added factors of the pandemic and severe drought. She hesitates to call Maji Yaje Kwanza a failure, but it has been a humbling, sometimes numbing, experience from which she has learned many valuable things, including the importance of civic engagement to drive local change: “I will say, this project has caused quite a stir in the community, as well as the local political scene. The team and I drove out to another school 25 kilometers away and when we arrived they already knew who we were. I try to see the silver lining of that, because the truth is that local leadership will only serve the people if the people hold them accountable. That is a global issue. And sometimes, we get so used to things being broken that we accept them as being the way they are. Change can’t be realized if it isn’t envisioned.”

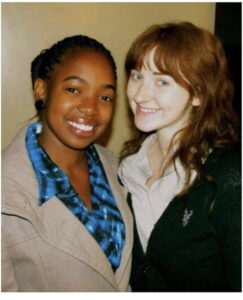

The most precious silver lining has been Ashley’s continuing relationship with Louisa’s 70-member extended family: “They are mine, and I’m theirs.” She recently returned from her first visit back to Kenya since the attempted borehole drilling in December 2018. This past year was filled with grief, with the passing of Louisa’s father and grandmother, both of whom Ashley was very close with. But this visit marked another new chapter: meeting Louisa’s 2-week-old baby boy, and his cousin, born two weeks apart. The irony was not lost on Ashley: “Right after we lost these two pillars in the family, two beautiful new souls came into our lives. And, in fact, a whole new generation of kids has blossomed in the nine years that I’ve known Louisa. I adore them. I was so grateful to get to be there at such a joyful time. It was a beautiful reminder that life is cyclical, and after loss there can still be life.”

As for Ashley’s life since the project, she spent a few years as a writing tutor for Cal Athletics and as a project manager for the Scholarships department of the Cal Alumni Association. After two years in Austin, Ashley has landed in Nashville, where she is employed as a nanny and is focusing on singing and songwriting. She is currently working on solo project of songs inspired by kids, including two songs she recorded this summer in Kenya with Louisa’s cousin and uncle, who are both musicians.

For Ashley, water has, indeed, been the first of many things.